|

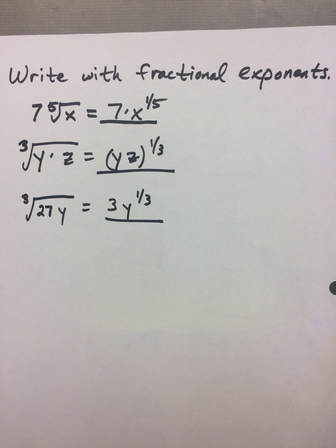

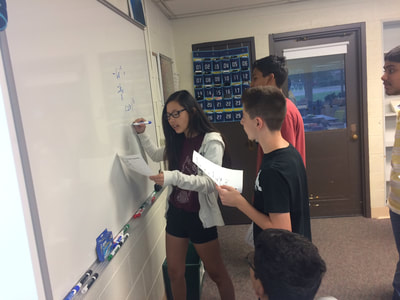

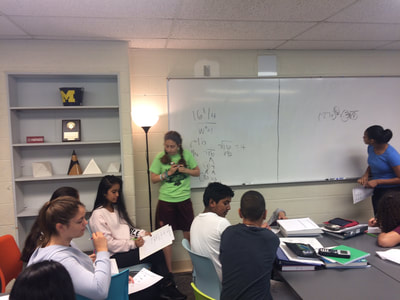

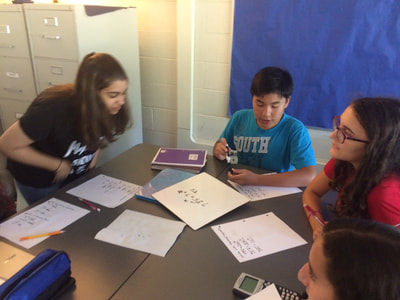

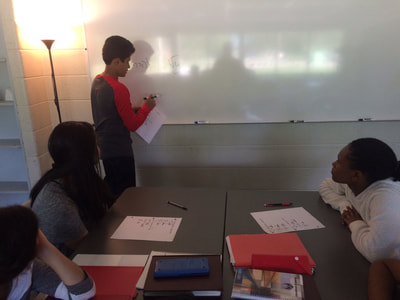

This week in my freshmen integrated math class, the students needed to review and comprehend laws of exponents. I created a sheet with three different types of problems (see figure below). I gave the students 5 minutes to read and annotate the document. Many of the comments I saw were pretty typical: "Why isn't the three inside the radical?", "Does eight to the zero just disappear?", "What does 16^(1/4) mean exactly?" The students then discussed with their groups the various questions and comments that they originally wrote down. As I listened to the conversations, I began to realize that the understanding of the concepts and rules of exponents was not going quite as I expected. One of the students asked me, "Mr. Watson, are you going to go over these?" Translation: "Mr. Watson, are you going to go up to the front and go through each one for us?" I did not think that going to the front and lecturing was the right thing to do at that point in time. Sure, I would go up and present the rules, answers, and be proud of the clarity of math that I shared with the students, but going by the old phrase 'the person doing the talking is the person doing the learning,' I realized at that point we needed a different direction as a class. In the past, I may have given in and spent the next twenty minutes spoon-feeding the information. Instead, I tried something different.  I asked the class the following question, "Which of you understand all nine problems, and no longer have questions?" Six students joined me at the front and I called them the 'group leaders.' At that point, I used the Team Shake app on my phone to generate six teams (it literally takes a few seconds to generate the teams). I then assigned one group leader per group. I explained to the group leaders that they needed to take their group to some space in the room to ask and answer questions about the different exponent rules and examples that we were learning about. All the groups went to various places around the room - some took small white boards for their group and some gathered around the large white board. The group leaders then began to ask and answer questions to their team. The conversations began to grow and soon the groups were off and running. I was sure to listen in as the groups discussed, debated, and collaborated on the problems and ideas. It was invigorating to say the least. I was a guide for the groups - giving proper direction when the groups veered off track, answering questions at the appropriate times, and ensuring that all team members were involved in the learning. When the groups told me they were 'finished', I gave them some extra practice problems. I had the group leaders come up so we could give them a round of applause for leading the groups. After that I told everybody to go back to their home tables, and I explained to them, "In your home tables, take a few minutes and formulate any lingering questions that you may have. You are going to have a chance to ask me these questions so be sure they are good ones!" The groups discussed for a few minutes and when I could tell they were ready, I set my timer for ten minutes. I then told them "You now have 10 minutes to ask me the lingering questions. Let's do this!" There were questions, but I found that they were much deeper than I had expected. Here are some examples:

I believe that both of these questions came to light because the mechanics and rules were discussed, explored, and answered in their groups. Then they had time to ask me more of 'wonder' type questions.  Which of the eight cultural forces were leveraged during this class period? Here is one view: Expectations: Student independence was actively cultivated by having them work in groups with group leaders and to be actively engaged with each other. The students directed most of the activity. Language: During the lesson, I tried to give specific action-oriented feedback, such as, "I like how you explained the fractional exponent rule here and the example that you used" and "This was a clever way to explain this to your group - it seemed like they really grasped the concept." Time: I really tried to monitor the amount of time that I talked during this lesson - it was limited to small chunks of time. The most that I was at the front talking at the class was the 10 minute session near the end. Interactions: Groups acted independently and many times I just listened in to hear their thinking. Many students challenged ideas, not the people pitching the ideas. Opportunities: Students got the opportunity to direct their own learning in their groups. The group leaders led the way, but all group members were allowed to questions and direct what was happening. In a previous article, I spoke of a "lawn" math classroom vs. a "ravine" math classroom. I believe that this class period was definitely exploring the "ravine!"

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

AuthorJeff Watson is a Math teacher at the University Liggett School in Grosse Pointe Woods, MI. His work as a software engineer made him realize the need for problem solvers and critical thinkers in the workplace today. Jeff believes that the secondary math classroom should be a place of critical thinking, collaborative learning, and exploration which will cultivate the problem solvers and thinkers needed today. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed