|

At the 2017 Project Zero classroom in Cambridge, MA, David Perkins described a setting in which he was sitting on a well-manicured, perfectly green lawn, while a few feet away at the edge there existed a colorful, wild, interesting ravine, full of life and questions. He asked the participants: 'Is your classroom a lawn - well manicured, predictable, and neat, or is it a ravine - wild, messy, with organized chaos?'  This got me thinking about my own classroom, of course, and how for many years, my room primarily fit the description of a well-manicured 'lawn.' But what does a 'lawn' math classroom look like? What are its characteristics? I came up with a short list:

After thinking about this for a while, I remember an example math classroom from "Creating Cultures of Thinking: The 8 Forces We Must Master to Truly Transform Our Schools" by Dr. Ron Ritchhart, a member of the Project Zero team at Harvard University. In it, Dr. Ritchhart describes a math classroom in which he "had a hard time finding moments when students were truly engaged in any thinking" (Ritchhart, p. 39). The teacher was described as very personable, and was reliably consistent with her students, but that it seemed the students "made an internal calculation regarding how much attention needed to be paid to complete the homework successfully or prepare for the looming test" (Ritchhart, p. 40). This classroom seems to be primarily a 'lawn' classroom, with little, if any, ravine characteristics.  Now, to be clear, there is nothing inherently 'wrong' with a having a 'lawn' classroom some of the time, perhaps for part of a class period, or for an entire class period. There needs to be a good balance. The issue, in my opinion, is when a math classroom becomes a lawn day after day, and week after week, because this causes the teacher to do a majority of the critical thinking and the rich opportunities for student learning are lost. This idea of lawn versus ravine ties nicely with the eight cultural forces that make up the Cultures of Thinking (CoT) framework: expectations, language, time, modeling, opportunities, interactions, routines, and environment. If properly leveraged, the eight cultural forces could create a classroom culture that mimics the 'ravine', with some 'lawn'. However, if left to fester and not leveraged properly, the classroom could become primary a 'lawn', with little 'ravine': predictable, well-managed, but lacking the deep thought necessary for 21st century learning. So, how do the eight cultural forces 'look' in a math classroom that is primarily a 'lawn'? Let's take a look at each force: Expectations: Many things are expected of students in this type of classroom. The teacher may say things like:

Language: The key language moves to create a culture of thinking that Ritchhart describes are the language of thinking, community, identity, initiative, mindfulness, praise and feedback, and listening. In a 'lawn' classroom, some of these key language moves may not exist at all, or may be counter-productive to a culture of thinking. For example, if a teacher is continuously the sage and provider of information in a classroom, then students may never hear the language of community and identity. Furthermore, the language of praise and feedback may strictly be a language of praise without a language of feedback. Generic praise comments might include 'good job', 'great', 'brilliant', instead of action-oriented feedback such as 'I like how you completed the square here - I have not seen that before' or 'your graphs here are very detailed and it took very little time for me to get a clear picture of what is happening.' Time: In a lawn math classroom, time may be used very well and there may not be a second to spare, but the time spent may not be on critical thinking. For example, if a lot of time is spent in lecture or sit-and-get mode, then time is allocated and used, but students are merely scribes at that point, with little or no thinking being accomplished. If this is the case, there might not be enough time for students to process ideas. As a general rule, a teacher should not talk for more than ten minutes at a time in order to give students processing time. Modeling: The cultural force of modeling as described by Ritchhhart is the teacher as a role model of learning and thinking; in a lawn classroom the modeling may be predominantly instructional modeling which consists of the teacher showing techniques and methods to 'show the work' and 'get the right answer.' As a role model of learning, the teacher should be modeling how to take risks and reflect on the learning. It's ok for a math teacher to say, 'I'm not sure why dividing by 5 stretches the graph - I need to look into that more. It does seem like the graph should shrink. Why don't we do some research and we can talk about it next time and coordinate our ideas?' Opportunities: What opportunities are 'lawn' math classrooms providing for students? Ritchhart states that 'opportunities that teachers create are the prime vehicles for propelling learning in classrooms.' In 'lawn' math classrooms, the opportunities for rich thinking in which the student examines, notices, observes, identifies, uncovers complexities, and captures the essence of something may be limited. If a math classroom consists of homework check followed by direct instruction, day in and day out, then it is very possible that a student does not think at all, outside of the elementary tasks of 'paying attention' and 'taking notes.' As a math teacher, do you take quality time when planning to ensure that your students have rich opportunities?  Interactions: A 'lawn' math classroom may consist of a lot of QRE interactions, which stands for Question-Respond-Evaluate - the teacher asks a question, a student responds, then the teacher evaluates that answer. This results in a 'Ping-Pong match back and forth between the teacher and a single student, leaving much of the class out of the interaction' (Ritchhart, p. 212-13). The interactions that should be fostered are ones where the students are pushed to reason and think beyond a simple answer. Routines: A 'lawn' math classroom may be littered with procedural routines, for example:

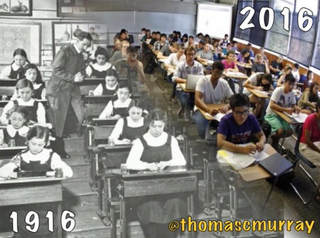

Environment: Take a look at the image created by Thomas Murray ([email protected]) on the left. Does this look familiar? Not much has changed if you compare the class from 1916 to the one from 2016, yet the world around us has changed in so many ways. In many math classrooms, desks in rows are still a reality. Is there a place for this? Sure there is, perhaps during tests or at a time where a mathematical procedure needs to be shown. However, this should not be the primary setup; it should be changed to allow students to have richer learning opportunities, interactions, collaborations, and discussions. So, what is a 'ravine', and what do the eight forces 'look' like in that type of classroom? Stay tuned as I will look at that in the next blog post!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

AuthorJeff Watson is a Math teacher at the University Liggett School in Grosse Pointe Woods, MI. His work as a software engineer made him realize the need for problem solvers and critical thinkers in the workplace today. Jeff believes that the secondary math classroom should be a place of critical thinking, collaborative learning, and exploration which will cultivate the problem solvers and thinkers needed today. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed